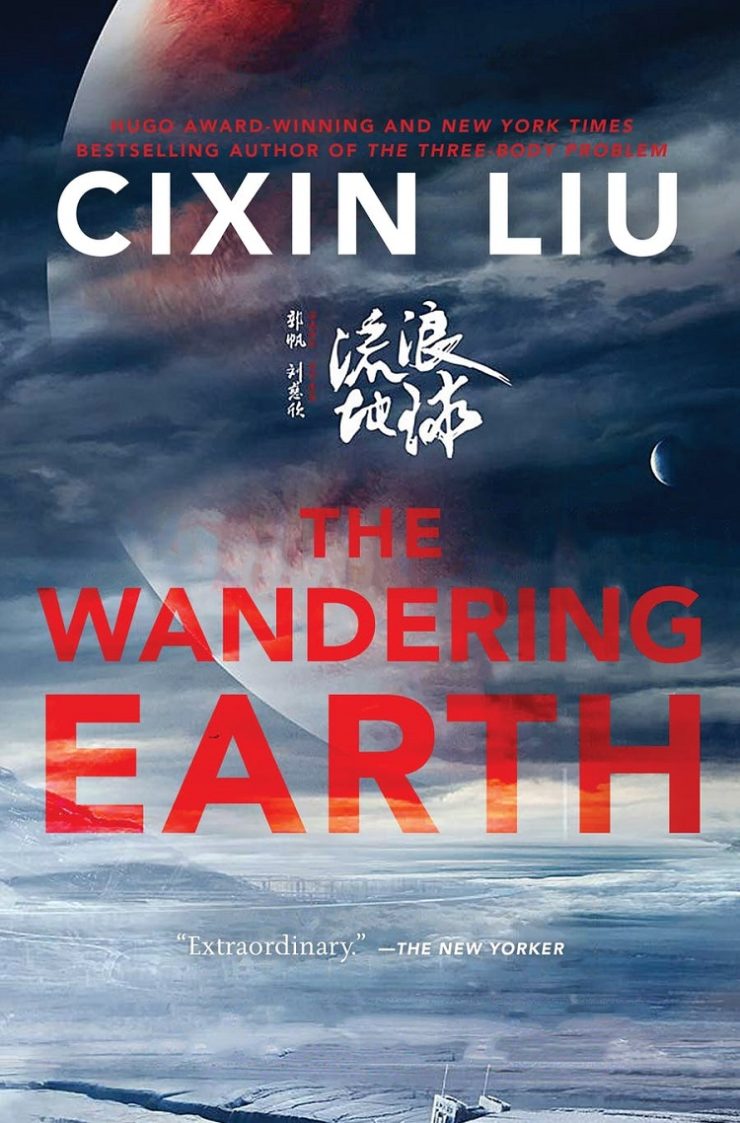

We are overjoyed to be sharing “With Her Eyes” by Cixin Liu, which will also appear in The Wandering Earth, out on October 12th!

Prologue

Two months of nonstop work had left me exhausted. I asked my director for a two-day leave of absence so that I could go on a short trip and clear my mind. He agreed, but only on the condition that I take a pair of eyes along with me. I accepted, and he took me to pick them up from the Control Center.

The eyes were stored in a small room at the end of a corridor. I counted about a dozen pairs. The director gestured to the large screen in front of us as he handed me a pair and introduced me to the eyes’ owner, a young woman who appeared to be fresh out of university. She was staring blankly at me. The woman’s puffy spacesuit made her appear even more petite than she probably was. She looked miserable, to be honest. No doubt she had dreamt of the romance of space from the safety of her university library; now she faced the hellish reality of the infinite void.

‘I’m really sorry for the inconvenience,’ she said, bowing apologetically. Never in my life had I heard such a gentle voice. Her soft words seemed to float down from space like a gentle breeze, turning those crude and massive orbiting steel structures into silk.

‘Not at all. I’m happy to have some company,’ I replied sincerely. ‘Where do you want to go?’

‘Really? You still haven’t decided where you’re going?’ She looked pleased. But as she spoke, my attention was drawn to two peculiarities.

Firstly, any transmission from space reaches its destination with some degree of delay. Even transmissions from the Moon have a lag of two seconds. The lag time is even longer with communications from the Asteroid belt. Yet somehow her answers seemed to arrive without any perceptible delay. This meant that she had to be in LEO: low-Earth orbit. With no need for a transfer mid-journey, returning to the surface from there would be cheap and quick. So why would she want me to carry her eyes on a vacation?

Her spacesuit was the other thing that seemed odd. I work as an astro-engineer specializing in personal equipment, and her suit struck me as odd for a couple of reasons. For one thing, it lacked any visible anti-radiation system, and the helmet hanging by her side appeared to lack an anti-glare shield on its visor. Her suit’s thermal and cooling insulation also looked incredibly advanced.

‘What station is she on?’ I asked, looking over at my director.

‘Don’t ask.’ His expression was glum.

‘Leave it, please,’ echoed the young woman on the screen, abjectly enough to tug at my heartstrings.

‘You aren’t in lockup, are you?’ I joked.

The room displayed on the monitor looked exceedingly cramped. It was clearly some sort of cockpit. An array of complex navigation systems pulsed and blinked around her, yet I could see no windows, not even an observation monitor. The pencil spinning near her head was the only visible evidence that she was currently in space.

Both she and the director seemed to stiffen at my words. ‘OK,’ I continued hurriedly. ‘I won’t ask about things that aren’t my concern. So where are we going? It’s your choice.’

Coming to a decision appeared to be a genuine struggle for her. Gloved hands gripped in front of her chest, she shut her eyes. It was as though she were deciding between life and death, or as if she thought the planet would explode after our brief vacation. I couldn’t help but chuckle.

‘Oh, this isn’t easy for me. Have you read the book by Helen Keller Three Days to See? If you have, you’ll understand what I’m talking about!’

‘We don’t have three days, though. Just two. When it comes to time, modern-day folk are dirt-poor. Then again, we’re lucky compared to Helen Keller: in three hours, I can take your eyes anywhere on Earth.’

‘Then let’s go to the last place I visited before leaving!’

She told me the name of the place. I set off, her eyes in my hand.

Chapter 1

Grassland

Tall mountains, plains, meadows and forest all converged at this one spot. I was more than two thousand kilometers from the space center where I worked; the journey by ionospheric jet had taken all of fifteen minutes. The Taklamakan lay before me. Generations of hard graft had transformed the former desert into grassland. Now, after decades of vigorous population control, it was once again devoid of human habitation.

The grassland stretched all the way to the horizon. Behind me, dark green forests covered the Tian Shan mountain range. The highest peaks were capped with silvery snow. I took out her eyes and put them on.

These ‘eyes’ were, in reality, a pair of multi-sensory glasses. When worn, every image seen by the wearer is transmitted via an ultra-high-frequency radio signal. This transmission can be received by another person wearing an identical set of multi-sensory glasses, letting them view everything that the first individual sees. It’s as if the transmitter is wearing the recipient’s eyes.

Millions of people worked year-round on the Moon and the Asteroid Belt. The cost of a vacation back on Earth was astronomical – pardon the pun – which is why the space bureau, in all their stinginess, designed this little gadget. Every astronaut living in space had a corresponding pair of glasses planet-side. Those on Earth lucky enough to go on a real-life vacation would wear these glasses, allowing a homesick space-worker to share the joy of their trip.

People had originally scoffed at these devices. But as those willing to wear them received significant subsidies for their travels they actually became quite popular. These artificial eyes grew increasingly refined through the constant use of the most cutting-edge technology. The current models even transmitted their wearers’ senses of touch and smell by monitoring their brainwaves. Taking a pair of eyes on vacation became an act of public service among terrestrial workers in the space industry. Not everyone was willing take an extra pair of eyes with them on vacation, citing reasons such as invasion of privacy. As for me, I had no problem with them.

I sighed deeply at the vista before my eyes. From her eyes, however, came the gentle sound of sobs.

‘I have dreamed of this place ever since my last trip. Now I’m back in my dreams.’ came her soft voice, drifting out from her eyes. ‘I feel like I am rising from the depths of the ocean, like I’m taking my first breath of air. I can’t stand being closed in.’

I could actually hear her taking long, deep breaths.

‘But you aren’t closed in at all. Compared to the vastness of space around you, this grassland might as well be a closet.’

She fell silent. Even her breathing seemed to have stopped.

I continued, if only to break the silence.

‘Of course, people in space are still closed in. It’s like when Chuck Yeager described the Mercury astronauts as being—

‘Spam in a can.’ She finished the thought for me.

We both laughed. Suddenly she called out in surprise.

‘Oh! Flowers! I see flowers! They weren’t here last time!’ Indeed, the broad grassland was adorned with countless small blooms. ‘Can you look at the flowers next to you?’

I crouched and looked down.

‘Oh, how beautiful! Can you smell her? No, don’t pick her!’

Left with little choice, I had to lie almost flat on my belly to pick up the flower’s light fragrance.

‘Ah, I can smell it too! It’s like she’s sending us a delicate sonata.’

I shook my head, laughing. In this age of ever-changing fads and wild pursuits, most young women were restless and impulsive. Girls as dainty as this particular specimen, who was practically moved to tears at the sight of a flower, were few and far between.

‘Let’s give this little flower a name, shall we? Hmm… We’ll call her Dreamy. How about that one? What should we call him? Umm, Raindrop sounds good. Now go to that one over there. Thanks. Her petals are light blue – her name should be Moonbeam.’

We went from flower to flower in this way, first looking, then smelling and finally naming them. Utterly entranced, she kept at it with no end in sight, all else forgotten. I, however, soon grew bored to death of this silly game, but by the time I insisted that we stop, we had already named over a hundred flowers.

Looking up, I realized we had wandered a good distance, so I went back to retrieve my backpack. As I bent down to pick it up, I heard a startled shout in my ear.

‘Oh no! You crushed Snowflake!’

I gingerly propped the pale little wildflower back up. The whole scene suddenly felt comical. Covering a flower with both hands, I asked her, ‘What are their names? What do they look like?’

‘That one on the left is Crystal. She’s white, too, and has three leaves on her stem. To the right we have Flame. He’s pink, with four leaves. The top two leaves are separate, and the bottom two are joined.’

She got them all right. Actually, I felt somewhat moved.

‘See? We all know each other. I’ll think of them over and over again during the long days to come. It’ll be like retelling a beautiful fairy tale. This world of yours is absolutely wonderful!’

‘This world of mine? It’s your world too! And if you keep acting like a temperamental child, those anal-retentive space psychologists will make sure you’re grounded on it for the rest of your life.’

I began to roam aimlessly about the plains. It wasn’t long before I came across a small brook concealed in the thick grass. I decided to forge ahead, but her voice called me back.

‘I want to reach into that stream so much.’

Crouching, I put my hands into the water. A cool wave of refreshment flowed through my body. I knew she would feel it too, as the ultra-high-frequency waves carried the sensation into the far reaches of space. Again I heard her sigh.

‘Is it hot where you are?’ I was thinking of that cramped cockpit and her spacesuit’s oddly advanced insulation system.

‘Hot,’ she replied. ‘As hot as hell.’ Her tone changed. ‘Hey, what’s that? The prairie wind?’ I had taken my hands from the water, and the gentle wind was cool against my damp skin. ‘No, don’t move. This wind is heavenly!’ I raised both hands to the breeze and held them there until they were dry. At her request, I dipped my hands back into the brook and then lifted them into the wind. Again it felt divine, and again we shared the experience. We idled away a long while like this.

I set out again, silently wandering for a while. I heard her murmur, ‘This world of yours is truly magnificent.’

‘I really wouldn’t know. The grayness of my life has dulled it all.’

‘How could you say that? This world has so many experiences and feelings to offer! Trying to describe them all would be like trying to count the drops of rain in a thunderstorm. Look at those clouds on the horizon, all silvery-white. Right now they look solid to me, like towering mountains of gleaming jade. The meadow below, on the other hand, looks wispy, as if all the grass decided to fly away from the earth and become a green sea of clouds. Look! Look at the clouds floating past the sun! Watch how majestically the light and shadows shift and twist over the grass! Do you honestly feel nothing when you see this?’

Wearing her eyes, I roamed the grassland for an entire day. I could hear the yearning in her voice as she looked at each and every flower, at every blade of grass, at every beam of sunlight leaping through the prairie and as she listened to all the different voices of the grassy plains. The sudden appearance of a stream, and of the tiny fish swimming within it, would send her into fits of excitement. An unexpected breeze, carrying with it the sweet fragrance of fresh grass, would bring her to tears… Her feelings for this world were so rich that I wondered whether something was wrong with her state of mind.

Before sunset, I made my way to a lonely white cabin standing forlornly on the grassland. It had been set up as an inn for travelers, although I seemed to be its first guest in quite some time. Besides myself, the cabin’s only other resident was the glitchy, obsolete android that looked after the entire inn. I was as hungry as I was tired, but before I had a chance to finish my dinner, my companion suggested that we go outside right away to watch the sun set.

‘Watching the evening sky gradually lose its glow as night falls over the forest – it’s like listening to the most beautiful symphony in the universe.’

Her voice swelled with rapture. I dragged my leaden feet outside, silently cursing my misfortune.

‘You really do cherish these common things,’ I told her on our way back to the cabin. Night had already fallen, and stars shone in the sky.

‘Why don’t you?’ she asked. ‘That’s what it means to truly be alive.’

‘I can’t really find any satisfaction in those things. Nor can most other people. It’s too easy to get what you want these days. I’m not just talking about material things. You can surround yourself with blue skies and crystal-clear waters just like that. If you want the peace and tranquility of the countryside or a remote island, you barely even need to snap your fingers. Even love. Think of how elusive that was for previous generations and how desperately they chased it, and now it can be experienced through virtual reality, at least for a few moments at a time.

‘People don’t cherish anything now. They see a platter of fruit an arm’s length away, only to take a bite out of each piece before throwing the rest away.’

‘But not everyone has such fruits within reach,’ she said quietly.

I felt my words had caused her pain, but I wasn’t sure why. The rest of the way back, we said nothing more.

I saw her in my dreams that night. She was in her spacesuit, confined to that tiny cockpit. There were tears in her eyes. She reached out to me, calling out, ‘Take me outside! I don’t want to be closed in!’ I awoke with a start and realized that she really was calling me. I was looking up at the ceiling, still wearing her eyes.

‘Please, will you take me outside? Let’s go see the Moon. It should be up by now!’

My head seemed to be filled with sand as I reluctantly pulled myself out of bed. Once outside, I discovered the Moon had indeed just risen; the night mist lent it a reddish tinge. The vast wilderness below was sound asleep. Pinprick glows from countless fireflies floated through the hazy ocean of grass, as though Taklamakan’s dreams were bleeding into reality.

Stretching, I spoke to the night sky. ‘Hey, can you see where the Moon is shining from your position in orbit? What’s your ship’s position? Tell me, and I might even be able to see you. I’m positive your ship’s in LEO.’

Instead of answering me, she began humming a song. She stopped after a few bars and said, ‘That was Debussy’s “Clair de Lune”.’

She continued humming, seemingly forgetting that I was still listening on the other end – or that I even existed. From orbit, melody and moonlight descended upon the prairie in unison. I pictured that delicate girl in outer space: the silvery Moon shining from above, the blue Earth below. She flew between the two, smaller than a pinpoint, her song dissolving into moonlight…

When I returned to bed an hour later, she was still humming. I had no idea if it was still Debussy, but it made no difference. That delicate music fluttered through my dreams.

Some time later – I’m not sure how long – her humming turned into shouting. Her cries stirred me from sleep. She wanted to go outside again.

‘Weren’t you just looking at the Moon?’ I was angry.

‘But it’s different now. Remember the clouds in the west? They might have floated over by now. The Moon will be darting in and out of the clouds; I want to see the light and shadows dance on the plains outside. How beautiful that must look. It’s a different kind of music. Please, take my eyes outside!’

My head throbbed with anger, but I went out. The clouds had floated on, and the Moon was shining through them. Its light filtered hazily over the grassland. It was as though the Earth were pondering deep and ancient memories.

‘You’re like a sentimental eighteenth-century poet. Tragically unfit for these times. Even more so for an astronaut,’ I said, peering into the night sky. I took off her eyes and hung them from a branch of a nearby salt cedar. ‘If you want to look at the Moon, you can do it by yourself. I really need to sleep. Tomorrow I have to get back to the space center and continue my woefully prosaic life.’

That soft voice whispered from her eyes, but I could no longer hear what she was saying. I went back to the cabin without another word.

It was daytime when I awoke. Dark clouds covered the sky, shrouding the Taklamakan in a light drizzle. The eyes were still hanging from the tree, mist covering the lenses. I carefully wiped them clean and put them on. I assumed that after watching the Moon for an entire night she would be fast asleep by now. However, I heard her sobbing quietly. A wave of pity overwhelmed me.

‘I’m really sorry. I was just too tired last night.’

‘No, it isn’t you,’ she said between sobs. ‘The sky grew overcast at half past three. And after five o’clock, it started to rain…’

‘You didn’t sleep at all?’ I nearly shouted.

‘It started raining, and I… I couldn’t see the sun when it rose,’ she choked out. ‘I really wanted to see the sun rise over the plains. I wanted to see it more than anything…’

Something had melted my heart. Her tears flowed through my thoughts, and I pictured her small nose twitching as she sniveled. My eyes actually felt moist. I had to admit: she had taught me something over the past twenty-four hours, though I couldn’t put my finger on exactly what. It was hazy, like the light and shadows moving over the grasslands. My eyes now saw a different world because of it.

‘There’ll always be another sunrise. I’ll definitely take your eyes out again to see it. Or maybe I’ll see it with you in person. How does that sound?’

Her sobbing stopped. Suddenly she whispered to me.

‘Listen…’

I didn’t hear anything, but I tensed.

‘It’s the first bird of the morning. There are birds out, even in the rain.’ Her voice was solemn, as though she were listening to the peal of bells marking the end of an era.

Chapter 2

Sunset 6

My memories of this experience quickly faded once I had returned to my drab existence and busy job. When I remembered to wash the clothes I had worn during my trip – which was some time afterwards – I discovered a few grass seeds in the cuffs of my trousers. At the same time, a tiny seed also remained buried within the depths of my subconscious. In the lonely desert of my soul, that seed had already sprouted, though its shoots were so tiny they were barely perceptible. This may have happened unconsciously, but at the end of each grueling work day I could feel the natural poetry of the evening breeze stir against my face. Birdsong could catch my attention. I would even stand on the overpass at twilight and watch as night enveloped the city… The world was still dreary to my eyes, but it was now sprinkled with specks of verdant green – specks that grew steadily in number. Once I began to perceive this change, I thought of her again.

She began to drift into my idle mind and even into my dreams. Over and over again, I would see that cramped cockpit, that strangely insulated spacesuit… Later on, these things retreated from my consciousness. Only one thing protruded from the void: that pencil, drifting in zero gravity around her head. For some reason, I would see that pencil floating in front of me whenever I shut my eyes.

One day I was walking into the vast lobby of the space center when a giant mural, one that I had passed countless times before, suddenly caught my eye. The mural depicted Earth viewed from space; a gem of deepest blue. That pencil again floated before my mind’s eye, but now it was superimposed over the mural. I heard her voice again.

I don’t want to be closed in.

Realization flashed through my brain like lightning. Space wasn’t the only place with zero gravity!

I ran upstairs like a madman and banged on the Director’s door. He wasn’t in. Guided by what felt like a premonition, I flew down to the small room where the eyes were stored. The director was there, gazing at the girl on the large monitor. She was still inside that sealed-off cockpit, still wearing that ‘spacesuit’. The image was frozen; almost certainly a recording.

‘You’re here for her, I suppose,’ he said, still looking at the monitor.

‘Where is she?’ My voice boomed inside the small room.

‘You may have already guessed the truth. She’s the navigator of Sunset 6.’

The strength drained from my muscles and I collapsed onto the carpet. It all made sense now.

The Sunset Project had originally planned to launch ten ships, from Sunset 1 to Sunset 10. After the Sunset 6 disaster, however, the project had been abandoned.

The project was an exploratory flight mission like many before it. It followed the same basic procedures as each of the space center’s other flight missions. There was just one difference – the Sunset vessels were not headed to outer space. These ships were built to dive into the depths of the Earth.

One-and-a-half centuries after the first space flight, humanity began to probe in the opposite direction. The Sunset-series terracraft were its first attempt at this form of exploration.

Four years ago, I had watched the Sunset 1 launch on television. It was late at night. A blinding fireball lit up the heart of the Turpan Depression so bright it caused the clouds in Xinjiang’s night sky to glow with the gorgeous colors of dawn. By the time the fireball faded, Sunset 1 was already underground. At the center of this circle of red-hot, scorched earth now churned a lake of molten magma. White-hot lava seethed and boiled, hurling bright molten columns into the air… The tremors could be felt as far away as Urumqi as the terracraft burrowed through the planet’s inner layers.

Each of the Sunset Project’s first five missions successfully completed their subterranean voyages and returned safely to the Earth’s surface. Sunset 5 set a record for the furthest any human had traveled beneath the planet’s surface: 3,100 kilometers. It was a record that Sunset 6 did not intend to break, and with good reason. Modern geophysics had concluded that the boundary between the Earth’s mantle and core lay between 3,400 and 3,500 kilometers underground; this convergence is referred to academically as the ‘Gutenberg Discontinuity’. Breaching this boundary meant entering the planet’s iron-nickel core. Upon entering the core, the density of the surrounding matter would abruptly and exponentially increase to levels that went beyond the Sunset 6’s design specifications to navigate.

Sunset 6’s voyage began smoothly. It took the terracraft all of two hours to pass through the boundary between the Earth’s surface and mantle, also known as the ‘Moho’. After resting upon the sliding surface of the Eurasian plate for five hours, the ship began its slow three-thousand-plus kilometer journey through the mantle.

Space travel may be lonely, but at least astronauts can gaze at the infinity of the universe and the majesty of the stars. The terranauts voyaging through the planet, however, had nothing but the sensation of endlessly increasing density to guide them. All they could glean from peering into the terracraft’s holographic rearview monitors was the blinding glare of the seething magma following in their ship’s wake. As the craft plunged deeper, the magma would merge behind the aft section, instantly sealing the path that the ship had just forged.

A terranaut once described the experience. Whenever she and her fellow crew members shut their eyes, they would see the onrushing magma gather behind them, pressing down and sealing them in all over again. The image followed them like a phantom, and it made the voyagers aware of the massive and ever-increasing immensity of matter pressing against their ship. This sense of claustrophobia was difficult for those on the surface to comprehend, but it tortured each and every terranaut.

Sunset 6 completed each of its research tasks with flying colors. The craft traveled at approximately fifteen kilometers per hour; at this rate, it would require twenty hours to reach its target depth. Fifteen hours and forty minutes into their voyage, however, the crew received an alert. Subsurface radar had picked up a sudden increase of density in their vicinity, leaping from 6.3 grams per cubic centimeter to 9.5 grams. The surrounding matter was no longer silicate-based but primarily an iron-nickel alloy; it was also no longer solid but liquid. Despite having only achieved a depth of 2,500 kilometers, all signs currently indicated that Sunset 6 and its crew had entered the planet’s core.

The crew would later learn that they had chanced upon a fissure in the Earth’s mantle – one that led directly to its core. The fissure was filled with a high-pressure liquid alloy of iron and nickel from the Earth’s core. Thanks to this crack, the Gutenberg discontinuity had reached up one thousand kilometers closer to the Sunset 6’s flight path. The ship immediately took emergency measures to change course. It was during this attempt to escape that disaster truly struck.

The ship’s neutron-laced hull was strong enough to withstand the massive and sudden pressure increase to 1,600 tons per cubic centimeter, but the terracraft itself was comprised of three parts: a fusion engine at the bow, a central cabin, and a rear-mounted drive engine. When it attempted to change direction, the section linking the fusion engine to the main cabin fractured due to the density and pressure of liquid iron-nickel alloy that far exceeded the ship’s operating parameters. The images broadcast from Sunset 6’s neutrino communicator showed the forward engine splitting from the hull only to be instantly engulfed by the crimson glow of the liquid metal. A Sunset ship’s fusion engine fired a super-heated jet that cut through the material in front of the vessel. Without it, the drive engine could barely push the Sunset 6 an inch through the planet’s solid inner layers.

The density of the Earth’s core is startling, but the neutrons in the ship’s hull were even denser. As the buoyancy created by the liquid iron-nickel alloy did not exceed the ship’s deadweight, Sunset 6 began to sink towards the Earth’s core.

One-and-a-half centuries after landing on the Moon, humanity was finally capable of venturing to Mercury. It had been anticipated that we would travel from mantle to core in a similar time frame. Now a terracraft had accidentally entered the core, and, just like an Apollo-era vessel spinning off course and into the depths of space, the chance of a successful rescue was simply nonexistent.

Fortunately, the hull of the ship’s main cabin was sturdy, and Sunset 6’s neutrino communications system maintained a solid connection with the control center on the surface. In the year that followed, the crew of the Sunset 6 persisted in their work, sending streams of valuable data gleaned from the core to the surface.

Encased as they were in thousands of kilometers of rock, air and survival were the least of their worries – what they lacked more than anything else was space. They were pummeled by temperatures of over five thousand degrees Celsius and surrounded by pressures that could crush carbon into diamonds within seconds. Only neutrinos could escape the incredible density of the material in which the Sunset 6 was entombed. The ship was completely trapped in a giant furnace of molten metal. To the ship’s crew, Dante’s Inferno would depict a paradise. What could life mean in a world like this? Is there any word beyond ‘fragile’ that can describe it?

Immense psychological pressure shredded the nerves of the Sunset 6’s crew. One day, the ship’s geological engineer woke, leapt from his cot and threw open the heat-insulation door protecting his cabin. Even though this was only the first of four such doors, the wave of incandescent heat that washed in through the remaining three layers instantly reduced him to charcoal. To prevent the ship’s imminent destruction, the commander rushed to seal the open door. Although he was successful, he suffered severe burns in the process. The man died after making one last entry into the ship’s log.

With one crew member remaining, Sunset 6 continued its voyage through the planet’s darkest depths.

By now, the interior of the vessel was entirely weightless. The ship had sunk to a depth of 6,800 kilometers – the planet’s deepest point. The last remaining terranaut aboard the Sunset 6 had become the first person to reach the Earth’s core.

Her entire world had shrunk to the size of a cramped, stuffy cockpit. She had less than ten square meters to move around in. The ship’s onboard pair of neutrino glasses allowed her a small measure of sensory contact with the planet’s surface. However, this lifeline was doomed to be short-lived, as the craft’s neutrino communications system was nearly out of power. By now, the power levels were already too low to support the super-highspeed data relay that these sensory glasses relied on. In fact, the system had lost contact three months ago, just as I was taking the plane back from my vacation in the plains. By that time, her eyes were already stored inside my travel bag.

That misty, sunless morning on the plains had been her final glimpse of the surface world.

From then on, Sunset 6 could only maintain audio and data links with the surface. But late one night this connection had also ceased, sealing her permanently into the planet’s lonely core.

Sunset 6’s neutron shell was strong enough to withstand the core’s massive pressure, and the craft’s cyclical life support systems were fully capable of an additional fifty to eighty years of operation. So she would remain alive, at the center of the Earth, in a room so small she could traverse its area in less than a minute.

I hardly dared imagine her final farewell to the surface world. However, when the Director played the recording, I was shocked.

The neutrino beam to the surface was already weak when the message was sent, and her voice occasionally cut out, but she sounded calm.

‘…have received your final advisement. I’ll do all I can to follow the entire research plan in the days to come. Someday, maybe generations from now, another ship might find the Sunset 6 and dock with it. If someone does enter here, I can only hope that the data I leave behind will be of use. Please rest assured; I have made a life for myself down here and adapted to these surroundings; I don’t feel constrained or closed-in anymore. The entire world surrounds me. When I close my eyes, I see the great plains up there on the surface. I can still see every one of the flowers that I named.

‘Goodbye.’

Epilogue

A Transparent World

Many years have passed, and I have visited many places. Everywhere I go, I stretch out upon the Earth.

I have lain on the beaches of Hainan Island, on Alaskan snow, among Russia’s white birches and on the scalding sands of the Sahara. And every time the world became transparent to my mind’s eye. I saw the terracraft, anchored more than six thousand kilometers below me at the center of that translucent sphere, whose hull once bore the name Sunset 6; I felt her heartbeat echo up to me through thousands of kilometers. As I imagined the golden light of the sun and the silvery glow of the Moon shining down to the planet’s core, I could hear her humming ‘Clair de Lune’, and her soft voice:

‘…How beautiful that must look. It’s a different kind of music…’

One thought comforted me: even if I traveled to the most distant corner of the Earth, I would never be any farther from her.

“With Her Eyes” Copyright © 2021 by Cixin Liu